The Clockwork Universe

The Moment Determinism Was Born 🐣

Act 1: ~ 300 BCE

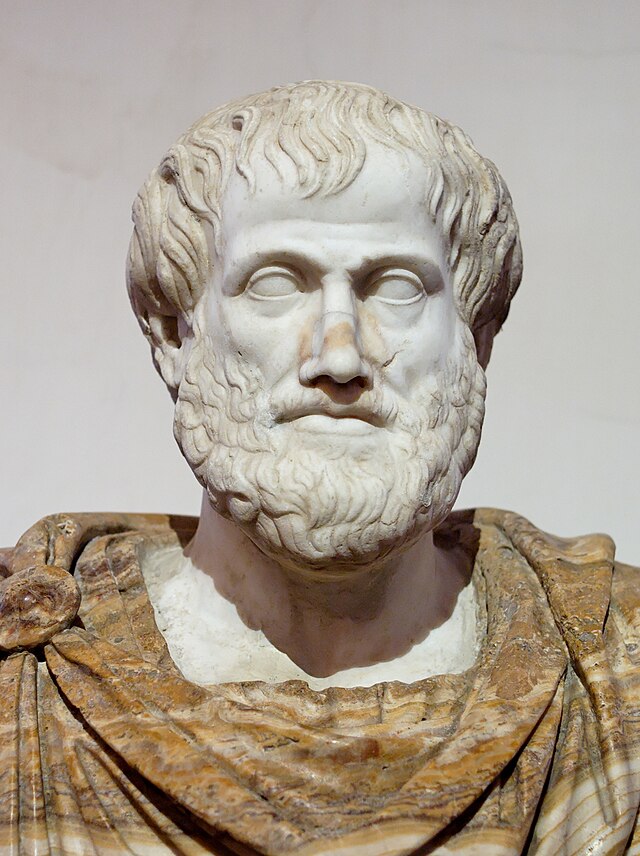

Somewhere in ancient Greece, a middle-aged fellow with a bushy beard, a wild hairdo (and, if you look closely, a crafty combover hiding a receding hairline) gathers a curious crowd of students around him (Lyceum, look it up).[1]

He gestures grandly moving his fingers that wore shiny golden rings and then declares,

There are four elements that make up our divine world: Earth, Fire, Air, and Water. Everything else? That’s the realm of the heavenly, the cosmic bodies above us! and that is the fifth element of the universe. The motion of these bodies are the only kind of natural motions.[2]

He continues,

Earth and water? They always want to go downwards. Fire and air? Upwards, of course! The stars and planets, though—they move in perfect circles, as if they’re performing a cosmic waltz. Rest every motion when you pull or push objects are unnatural motions, against nature's wish and are violent motions.

Our gentleman named, "Aristotle", had a notion that, if you stop pushing, everything just wants to chill out at rest. These notions about motions, believe it or not, were the building blocks of early thinking about how the universe works—nature’s very own rulebook for moving objects for about 2000 years!

Aristotle (After Lysippos). Public domain.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Act 2: The Rebel in the Library (c. 530 CE)

Fast-forward to about two hundred years, we must witness a maverick in Alexandria that wanted to break Aristotle's rules. John Philoponus, also known as "The Lover of Toil".

No images avilable that I could find (but no one is stopping us from imagining, I can paint a picture for you using my words, let's imagine a tired academic with ink-stained fingers and a very loud voice), his personality screams through his writing. Philiponus wasn't just a scholar; he was a disruptor. Some say he earned his nickname for writing 40 massive books; others say he was part of the Philoponoi. These were group of regular people who were so enthusiastic in the belief of chritian faith that they would meet and study it deeply and would join forces to attack pagan ideas.

Yes, he was regarded as a great intellectual person and as a rigorous logician but disliked by many perhaps even his peers.[3]

The "Bellows" Moment:

Bellows. Public domain.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Aristotle claimed that if you throw a stone, the air behind it keeps pushing it forward (Did he not see ever a small gust of wind opposing the item thrown?) Philoponus thought this was nonsense. He proposed a simple, "DIY" experiment:

Take a stone, place it on a surface, and use a pair of bellows to blow air behind it as hard as you can. Does the stone move? No. So why would the air move a stone in flight?

Very weak argument to be honest! Anyhow-"Impetus" was born.

Philoponus realized that the force isn't in the air; it’s implanted into the object by the thrower. He called this protopasti (imparted power), or what later thinkers called Impetus.[4]

And in Act 2, the notion of nature's element (Air) providing the push for motion has been busted by obvioulsly a chritian who took the role of divinity away from nature to human (Christ), with proposition that human agent provides the "impetues" not the nature.

Act 3: 1020 CE (Ibn Sīnā)

Ibn Sina/Avicenna Bust, left profile (cropped).jpg.

Source: National Library of Medicine, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

Fast forward about 500 years after Mr. Grumpy (😤), Smart-Guy John Philoponus was done blowing air at stones with bellows. We land in Central Asia, here we meet a man who was essentially The figure of the medieval intellectual world.

A man in a towering silk turban and a fur-lined robe, probably writing on a piece of parchment while bouncing on the back of a moving camel. Why the camel? Because Ibn Sīnā was the ultimate "scholar on the run." He was so smart that Sultans were constantly trying to either hire him or throw him in a dungeon—and he spent a fair amount of time experiencing both.

He wasn't just a doctor who wrote the medical textbook used for the next 600 years;[5] he was a guy obsessed with science.

Let's remember how Aristotle said things move only because the medium (like air) keeps shoving them. Ibn Sīnā looked at a soaring arrow and basically said, "Really! I don't think so." He may have come across ideas from John Philiponus and others like him or maybe not; but because the Arab world was so much the masters of trades during those period, this is more likely than not.

He developed a concept called Mayl (which is meant in some sense, "The Will to Keep Going").He leaned over his desk—or his camel—and declared:

If I throw a stone, I am handing that stone a gift: a certain amount of 'staying power.' It doesn't need the air to push it; it carries the push inside itself!

Basically the same concept as impetus from John Philiponus

But then, he took a giant leap into the "Clockwork" future. He came up with a thought experiment that would have made Aristotle so mad:

The Void. Ibn Sīnā argued that if you threw an object in a place with zero air (a vacuum), it wouldn't just stop because there was no air to push it. In fact, it would do the opposite. Without air to get in the way, that object would just... keep going forever.

You see aristotle totally denied the existence of void or zero. In his belief, nature detests void and so it would be immediately filled up by something. So he did not let his imagination go wild like Mr. Sina over here.

While he didn't have a calculator, he was describing the soul of what we now call Inertia. In his mind:

If the resistance is zero (like in the deep, dark void of space), the motion stays infinite.[6] Ibn Sīnā's "Mayl" was the first real gear placed into our Clockwork Universe. He realized that the stars and planets didn't need angels to keep pushing them along their tracks—they, just needed a "starting nudge" and a lack of friction to keep the cosmic gears turning until the end of time.

Act 4: ~1100 CE Ibn Malka al-Baghdadi

Oh Boy! You may never even have batted eyes on this name. But he was the first to completely negate Aristotle's dynamic theory.[7] Al-Baghdadi said that for a constant force applied to an object, it would not produce uniform motion (constant velocity).

Uniform Motion: If an object is moving, say, 5 meters every second, it will always move 5 meters per second. Such a motion is called uniform motion.

He proposed that constant force increases the velocity of the object with time (acceleration). Way ahead of Isaac Newton![8] He did not mathematically and beautifully formalize the concept as far as we know, though.

Act 5: 1638 (Galileo Galilei)

Galileo Galilei (Justus Sustermans, c.1640). Public domain.

Source: Royal Museums Greenwich, Wikimedia Commons

Galileo smuggled his final work Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Concerning Two New Sciences,[9] which contained most of his mature theories out of Italy from his house confinement punishment. Galileo was put under house arrest after his trial in 1633 with condemnation by the Roman Catholic Church, specifically the holy office (Inquisition) for vehement suspicion of heresy. He had previously promoted heliocentric (sun-at-the-center) ideas popularized by Copernicus[10] and was warned by the Church through an order to stop spreading and teaching them in 1616 based on the Church's declaration that heliocentricity is heretical. Well, this last work of his hence could not be published formally but it was smuggled and came to public attention that way. The guy just won't listen to the authorities!

Leaving the rebel nature of Galileo behind and reading into his logical, observational and scientific nature now, we can learn that Galileo had noticed that if you swing a pendulum—whether you give it a gentle nudge or a wild push—the time it takes to go back and forth stays the same![11] (As long as you don't go too wild.) This is very important because we have now moved beyond the concept from John Philoponus about a person providing Impetus for motion, and beyond Avicenna and Al-Baghdadi's ideas that constant force produces acceleration.

This work is deeper and more aligned to modern-day science. For first thing, it is based on a real-world experiment; not a thought experiment proposed by Al-baghdadi, regardless of it being developed based off real observations.

And this also involved measuring of time to unravel secrtes of motion. The observation and the experiment described are also loosely reproducible and that is one of the essences of scientific knowledge. Why would diffrent nudges make the pendulum swing as such the Time-Period (T) is the same? Very puzzling!

Time-Period (T) - Time to swing from one end to the other end of the pendulum and then back to the first end. A complete cycle of motion.

Okay, Go on Galileo, tell us more.

.. but if you make the pendulum longer, it swings slower. If you make it shorter, it swings faster.

The magic rule? The time it takes depends only on the length, not the weight or how hard you push!

In Galileo's words (well, sort of):

The Time-Period of a pendulums is only about how long it is."

And the math:

where, is sign of proportionality

where is the Time-Period of the "bob" moving from one extreme end of oscillation to the other end and then back, is the length of the pendulum. Thus, the time period is directly proportional to the square root of the length.

This kind of thinking is why Galileo gets called the “Father of Sciences.” His pendulum insights aren’t just central to physics—they’re a ticket to exploring the entire Clockwork Universe. And if you've ever read Foucault's Pendulum,[12] you know; pendulums have a knack for keeping secrets (and maybe, just maybe, the secrets of the world).

Act 6 - Finale: Pendulum Simulation

Experiment with the simple pendulum below! Adjust the mass and length to see how the period changes.

Remember: in an ideal pendulum, mass does NOT affect the period—only length does. See if you can verify this!

Simple Pendulum Explorer

Formula: Period T = 2π√(L/g) ≈ 2.457 seconds

Note: Mass does not affect the period in simple pendulum motion (for small angles). Try changing the length to see the period change!

Just using the simulation above you can learn a lot about vibrations, oscillations, time and even gravity. In fact you can make a leap from this Galileo's work to Einstein's works' conlusions.

Here are a few games to play with the above simulation.

Pendulum Quiz

References

- Britannica - Aristotle - Biographical information about Aristotle's life and teachings at the Lyceum.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Aristotle's Natural Philosophy - Overview of Aristotle's theories on motion, the four elements, and natural philosophy.

- Famous Scientists - John Philoponus - Life and contributions of John Philoponus to the concept of impetus theory.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Medieval Theories of Impetus - Examination of impetus theory and its development through medieval philosophy.

- Britannica - Avicenna (Ibn Sina) - Information on Ibn Sina's medical and scientific contributions.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Ibn Sina's Natural Philosophy - Overview of Ibn Sina's theory of Mayl and motion.

- Wikipedia - Abu'l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī - Historical account of Al-Baghdadi's critique of Aristotelian physics.

- Britannica - Mechanics - Overview of early concepts of force and acceleration.

- The Galileo Project - Stanford University - Primary sources and scholarly analysis of Galileo's works.

- Britannica - Copernican System - Historical context of the heliocentric model.

- Britannica - Galileo's Pendulum Experiments - Analysis of Galileo's discoveries including pendulum isochronism.

- Wikipedia - Foucault's Pendulum (novel) - Umberto Eco's postmodern novel inspired by pendulum physics.

Next Chapter

Ch 2: The Newton's Force — We meet Newton and his concept of force (way before Star-Wars)?